What Next? Education, of course.

Anglo-Indian School Education, especially.

7/31/20244 min read

To be honest, the average Anglo-Indian did not care too much about education, in general. This statement definitely held true right up to the middle 1960s, when, suddenly, young men and women of the Community learnt and decided that if they were to compete, they would have to be better equipped academically. The expected Railway jobs were gone, the days of Company secretaries were disappearing, entrepreneurial and business ventures were non-existent, or just start-ups and even the good old, multi-tasking, multi-talented, trained or middle-grade teacher was finding her space eroded by young people with nothing else but a paper degree in some subject or the other.

This is not to say that the young teacher-recruits were not willing to learn. But presence and panache and poise and proficiency and pertinence are not imbibed in under-graduate courses—at least, they were not part of the curriculum when I was a student in the twentieth century. It takes long years of practice and precept, observation and outlook, as well as the confidence—nay, zeal—to chart a new course, to develop a distinct and instinctive style, and to be humble enough to know that your best shot may often fall short. Teaching is learning and learning is part of teaching; trust me, dear Reader, for I had a good run for almost four decades, and if you acknowledge the source, which every good teacher must do, you will need to add another forty years that was the contribution of my teacher-mother.

The Anglo-Indian School system has, I think, been buried alive; not dead, but pushed into a corner by the mad rush to acquire knowledge. There seems to be no such thing as a holistic education today, for the enterprise is only successful if the student excels in various exams like NEET, JEE, UPSC, NET, SLET, GRE, SAT, and umpteen others. What’s worse, to enter school, parents need to step up and show that their toddlers already know the three R’s.

There are a few Anglo-Indian Schools (in name, at least) in the city of Chennai; the State of Tamil Nadu used to boast of 42 such Schools, but most of them now flourish because education today has expanded into big business. Of these, the Madras Schools kept to themselves, administered by the boss and his chosen few. The schools in the districts fared much better, I think, for they lacked the finesse of the metropolitan Schools.

After Independence and up to 1980, some schools were preferred because their philosophies were not grounded in aggrandizement. Think of Campion in Trichy, Stanes in Coimbatore, Montfort in Yercaud and Vestry in Trichy and you have the crème-de–la-crème of all-round Anglo-Indian education in its heyday.

Those were the days, my friends. When the world was younger, we thought they’d never end, but… Who can ever forget those days of guts and glory when the Quadrangular Sports were held. Each of the four Schools mentioned above organized and conducted the event of the year in rotation and the meet maintained its high standards—true to the Olympic spirit. When it finally dawned on the authorities that the girl students were not permitted to show their prowess, the R.S. Krishnan School in Trichy was admitted. Every School had its own hero and I’m sure some of my readers can recall the good times. Vestry had John Pamphilis, a sprinter who went on to achieve greatness on the National stage and B.S.Rathnam, an athlete who could compete and win in most track and field events. I still remember Robert Payne and his javelin-throwing, Bernard Vanspall and his long-distance running and Basil Johnson for his unique sprinting action. It was all great fun, and though I never was an active participant, I won the greatest prize of my life—my wife-to-be, who had come along with the Stanes team! My School has done so much for me, on and off the sports field and I will be forever grateful, because of the special dispensation that came my way.

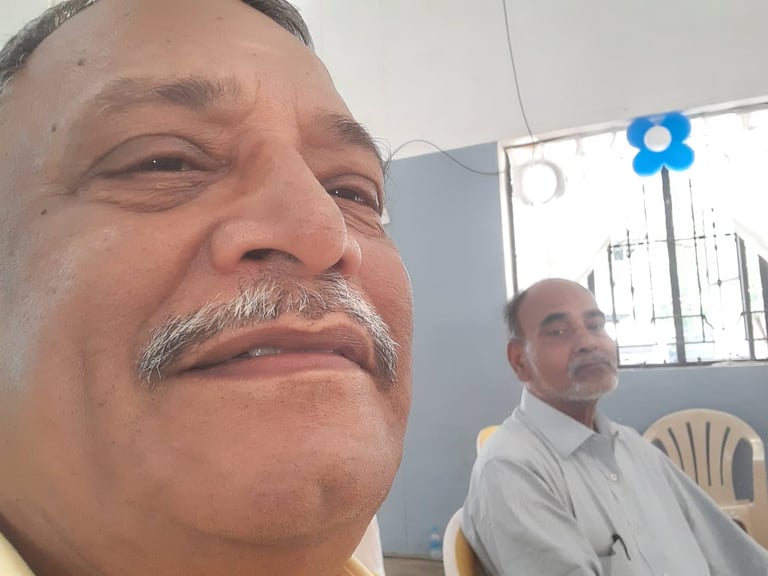

Students today get to spend 12 (or more, sometimes) years in a particular school. That’s why my case is one-of-a-kind. I spent 22 short years in Vestry, because my mother had been given quarters there. All the landmarks of my early life happened on campus and I never knew another home until I set up my own. I attended one College for my PUC and my Degree, shifted to another for my Masters and only after Madras wooed me did I leave my Home-cum-School. I go back, faithfully, to attend the Past Students Association annual Reunion, and always there is my close friend and batch-mate of 1968, Abdul. We’re old fogies now, but the call remains as strong as it ever was.

I was meant to be a teacher. Only a few days ago, a student of mine from more than 20 years back, called me, out of the blue, and expressed joy, hearing my voice again. When I was leaving my College in Salalah, two random students presented me with a plaque addressed to “Dear Teacher Brine”. I still consider it the greatest compliment ever paid to me, even if was unintended. If, actually, I could lap every shore as the salt-sea-water does, I will be satisfied.

As the poet prophesied, years ago:

“Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter”.